Collective Anxiety in Europe and the U.S.! How Far Ahead Is China's Battery Technology—More Than a Decade?

SongGaoTech Harnessing expertise in end-to-end integrated software and hardware customization, we translate your requirements into viable solutions.

August 26th, 2025

This is by no means an accident, but the inevitable outcome of a “highly forward-looking” long-term strategy—over more than a decade, China has consistently placed the lithium iron phosphate (LFP) battery technology route at the core of its priority development.

Over the past decade and more, China has carefully laid out a global strategic landscape in the field of electric vehicle batteries. Today, it has established an overwhelming advantage over Western manufacturers, becoming an insurmountable challenge for them.

From state-supported gigafactories to independent technologies for key materials, China has built what industry experts call an “almost moat-like” full-industry-chain barrier in the power battery sector, plunging the European and American markets into a “catch-up dilemma.”

In an exclusive interview with EETimes, Doron Myersdorf, CEO of Israeli battery technology company StoreDot, offered an incisive assessment of the current geopolitical and technological landscape. He pointed out that China’s current dominant position stems from a “highly forward-looking” long-term strategy—specifically, it took the lead in establishing the LFP battery as its core technology route more than a decade ago.

This strategic foresight fully leveraged China’s abundant iron reserves and the patent barriers that Chinese enterprises had established early on in the production of liquid fermion composite materials.

Global Layout of LFP and China’s Strategic Advantages

China’s strategic shift from nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC) to LFP batteries was by no means a simple material choice, but a carefully designed blueprint for global control. Myersdorf noted: “A long-term strategy was formulated as early as a decade ago, aiming to integrate existing supply chains, patent assets, and gigafactory production capacity. This vision has created China’s global dominance in the LFP field today.”

This strategic advantage is fully evident in the predicament of enterprises like Northvolt—once Europe’s hope for the battery industry. Despite massive investments, these enterprises have been unable to achieve economies of scale, let alone establish a competitive edge, partly due to their reliance on Chinese equipment and technology.

Beyond controlling raw materials, China has also achieved innovative breakthroughs within the LFP chemical system, significantly enhancing battery performance. By pioneering the application of large-sized LFP cells—a design that is unfeasible in NMC systems due to safety risks—Chinese enterprises have developed revolutionary architectures such as BYD’s “Blade Battery” technology, as well as “CTP (Cell to Pack),” “CTC (Cell to Chassis),” and “CTB (Cell to Body)” technologies.

These innovations have completely abandoned the traditional module structure and its supporting components—a design that is essentially a technical constraint of the NMC system. Myersdorf pointed out that this combination of “chemical system innovation + structural design breakthrough” has essentially given China an “almost monopolistic position in the LFP field,” building a “moat for dominance in the battery industry for at least the next decade.”

While NMC batteries still hold performance advantages in high-end vehicle models—offering longer range and faster charging speeds (e.g., the NMC silicon-based battery used in the Polestar 5 enables 10-minute fast charging)—LFP batteries, with their cost advantages, remain the absolute choice for China’s dominance in A/B/C-class passenger cars and commercial vehicles. Moreover, the global supply of LFP batteries is almost entirely dependent on Chinese manufacturers.

Another key material is graphite, used in battery anodes. China accounts for the majority of the global graphite market share, “controlling over 90% of the graphite on the market.”

While Myersdorf pointed out that graphite “may become a more breakable area”—as its overseas resource distribution is wider and its patent barriers are weaker than those of LFP—he admitted frankly: “This is yet another nail in the West’s coffin, and China has an extremely sophisticated layout in this regard.”

The Myth of Solid-State Batteries and Strategic Lag

Miscalculations in the West’s battery strategy toward China are common. Myersdorf noted: “There is a naive belief in the West—that as long as we bet on solid-state batteries, we can defeat China.”

Myersdorf pointed out that enterprises like QuantumScape and Solid Power are betting on solid-state battery technology, pursuing higher energy density and faster charging speeds.

However, this strategy has proven to have fundamental flaws. Due to high costs, solid-state batteries are likely to be confined to niche markets for a long time. “It will take at least one or two decades to achieve mass production, and an entirely new system of equipment and materials will be needed,” he emphasized specifically. “If we want to develop solid-state batteries, most of the existing gigafactories will become meaningless in most cases.” This assertion stems from the practical dilemma faced by QuantumScape, which had to build an entirely new production platform to manufacture solid-state battery separators.

In contrast, China has chosen to deeply cultivate existing lithium-ion technology: by continuously optimizing electrolyte formulations and safety mechanisms, it has not only achieved a stepwise reduction in costs but also built a complete supply chain barrier.

Myersdorf stated categorically: “In my view, the West has made a fundamental strategic mistake—we are obsessed with inventing the next generation of batteries, while China has chosen to improve existing technologies. Now, we are at least a decade behind China in the battery field.”

Beyond technical issues, a fundamental problem facing Europe is the “slow adoption of electric vehicles by traditional automakers.” Years of continuous investment in internal combustion engine technology have led to inertial thinking, making these manufacturers adopt electric vehicle production more passively than proactively.

The Power of Vertical Integration and the Rise of Chinese Electric Vehicles

For successful electric vehicle enterprises such as Tesla and BYD, their vertical integration strategy in battery production is a key differentiating factor. “Batteries account for approximately half of the total cost of a vehicle. It can be said that an electric vehicle is essentially a battery system equipped with a great deal of software and design solutions,” Myersdorf emphasized.

Western manufacturers usually separate vehicle production from battery production, which leads to “additional costs due to the existence of another intermediary link in battery production” and, more importantly, “they cannot control the relevant technologies.”

This comprehensive approach, often supported by the Chinese government, enables the realization of an “ultra-localized supply chain” and efficient vehicle assembly.

As a result, a large number of competitive Chinese cars have flooded the global market. Myersdorf witnessed this phenomenon firsthand in Israel—over the past year alone, “seven new Chinese automotive brands” have appeared on the streets, and people are actively purchasing these models. He pointed out that concerns about the quality of Chinese cars are fading, and the price gap between high-end electric vehicles from Mercedes-Benz and Zeekr even exceeds 200%.

This trend poses a “huge challenge” to Western countries—not only European countries but also the United States—because they “have failed to change their mindset to adapt to the development trend of electric vehicles.”

“The lack of strategy and chaos” has made the future of large European original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) uncertain. Myersdorf questioned: “Who knows if there will be any large profitable OEMs left in Europe in five years?”

Western Enterprises Turn to Overseas Markets Amid Domestic Policy Uncertainty

Domestic policy uncertainty has exacerbated the challenges for Western battery enterprises. U.S. battery material manufacturers such as Group14 are increasingly “turning to overseas markets” to seek manufacturing opportunities, stating that “domestic support for clean technology is weakening.”

Group14, a silicon-based battery material manufacturer, has fully taken control of its manufacturing operations in South Korea to achieve “direct access” to the Asian market. The company stated that “90% of battery production is within a four-hour flight from the region where its facilities are located.” Due to “tariff uncertainty and doubts about whether public funding support will be available,” the company has delayed the opening of its U.S. facilities.

Similarly, California-based Lyten acquired the remaining assets of bankrupt Swedish battery manufacturer Northvolt in Europe—including its main factory in Sweden, R&D facilities, and the site for its future gigafactory in Germany—at a “significant discount,” despite Northvolt’s previous valuation of USD 5 billion.

Lyten plans to resume operations immediately and rehire most of Northvolt’s employees, with the aim of supplying “European batteries” to customers such as Volvo and BMW—clients that had previously signed cooperation agreements with Northvolt.

Thomas Kavanagh, Head of the Battery Materials Division at Argus Media, summarized this view, stating: “It is logical for U.S. companies to shift their battery material investments to other regions… Due to unpredictable political cycles and consumer skepticism toward electrification, other regions have taken the lead over the U.S. in battery technology and innovation.”

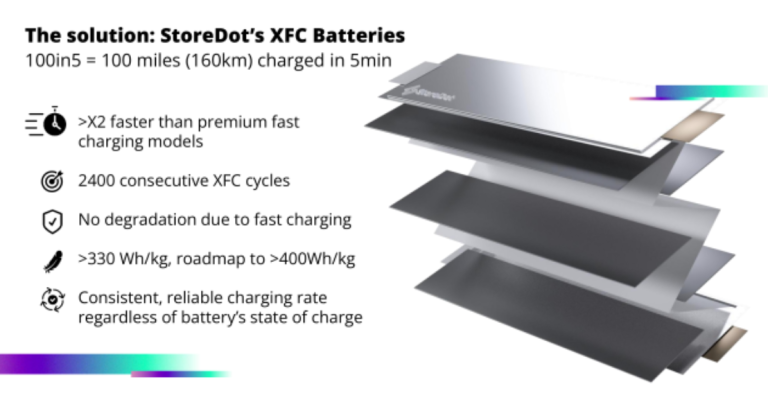

Against the backdrop of the reshaping of the global industrial landscape, enterprises such as StoreDot are actively advancing the development of advanced lithium-ion battery technology. StoreDot’s focus is on extreme fast-charging (XFC) batteries—a “key differentiator” for the large-scale adoption of electric vehicles (EVs)—with the goal of achieving “100 miles (160 kilometers) of charge in 5 minutes.” Its silicon-based XFC batteries promise to “maintain a stable and reliable charging rate regardless of the battery’s state of charge” and “avoid performance degradation caused by fast charging.”

Strategic investment in existing, proven lithium-ion chemistry technologies stands in stark contrast to the West’s former “naive belief” in entirely new battery architectures.

The current situation highlights the effectiveness of China’s well-orchestrated long-term strategy, which has secured China an absolute leading position in the electric vehicle battery market. For Western manufacturers, the future will require not only technological innovation but also fundamental shifts in strategic thinking and market strategies. At the same time, they must re-prioritize vertical integration and robust domestic industrial policies to avoid falling further behind.